Disorders of the Stomach and Duodenum

- related: GI

- tags: #GI

Dyspepsia

Clinical Features

Dyspepsia is a term used to describe epigastric pain. Associated symptoms can include early satiety, epigastric burning, nausea, and postprandial symptoms, including pain, bloating, or belching. Coexistent heartburn may be present, but it is not a primary symptom of dyspepsia. Recurrent or bothersome vomiting should raise concern for other conditions.

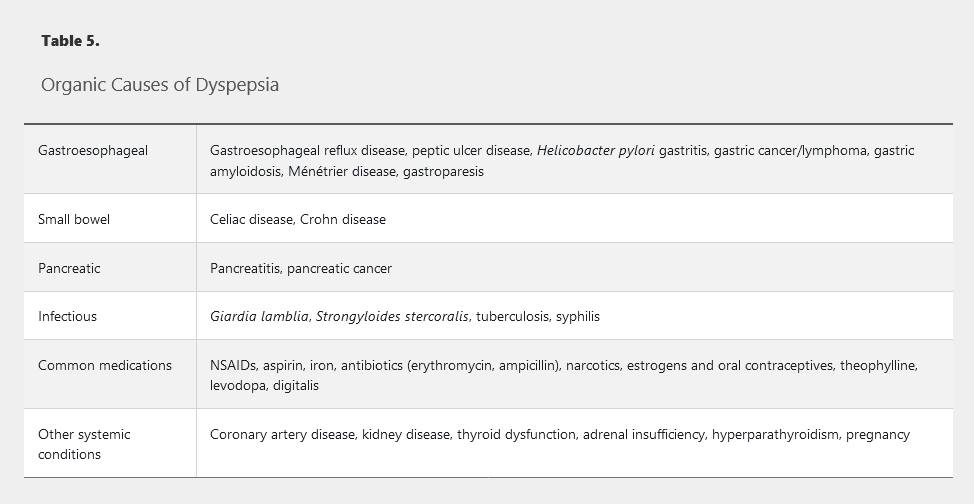

The list of possible organic causes of dyspepsia is extensive (Table 5); the most common conditions are peptic ulcer disease and gastroesophageal reflux disease (20% of patients with erosive esophagitis present with dyspepsia). If no organic cause of dyspepsia symptoms is identified after testing, the term functional dyspepsia applies.

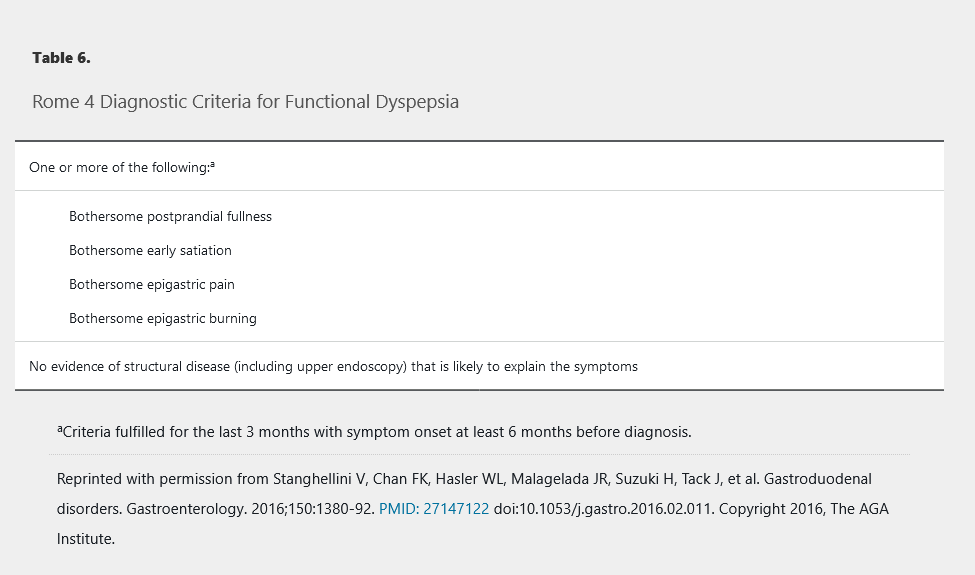

Functional dyspepsia represents a heterogeneous group of functional gastrointestinal disorders predominated by one or more upper gastrointestinal symptoms. Diagnostic criteria from the fourth Rome working group for functional gastrointestinal disorders are shown in Table 6. Functional dyspepsia can be further categorized into postprandial distress syndrome if the patient's predominant symptoms are meal-induced (Table 7), or epigastric pain syndrome if the predominant symptoms of epigastric pain or burning are unrelated to meals (Table 8).

Evaluation and Management

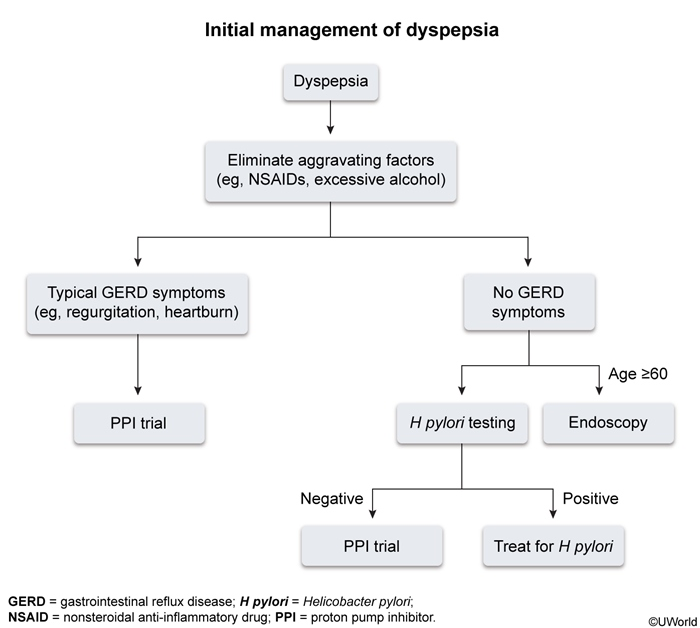

The approach to testing for dyspepsia should be based on patient age, severity of symptoms, and risk for gastric cancer. Upper endoscopy is commonly ordered to exclude upper gastrointestinal neoplasia; however, it is invasive and costly. Given the low incidence of malignancy and consideration for cost effectiveness in the evaluation of dyspepsia in younger adults, the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) and the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (CAG) have jointly recommended routine use of upper endoscopy only in patients aged 60 years and older to exclude malignancy. The ACG/CAG guidelines recommend against the routine use of upper endoscopy in patients younger than age 60 years, even in the presence of alarm features including weight loss, anemia, dysphagia, persistent vomiting, and severe symptoms, because these features are poor predictors of organic pathology, such as malignancy, peptic ulcer disease, or esophagitis. Consideration of endoscopy at a younger age is reasonable for patients at higher risk of malignancy, such as those with childhood years spent in a region where gastric cancer is endemic (Asia, Russia, and South America) or those with a positive family history.

For patients younger than age 60 years with dyspepsia symptoms, the ACG/CAG guidelines recommend noninvasive testing for Helicobacter pylori. Other testing, such as routine laboratory testing, screening for celiac disease, abdominal imaging, or gastric emptying, should be considered on an individual basis.

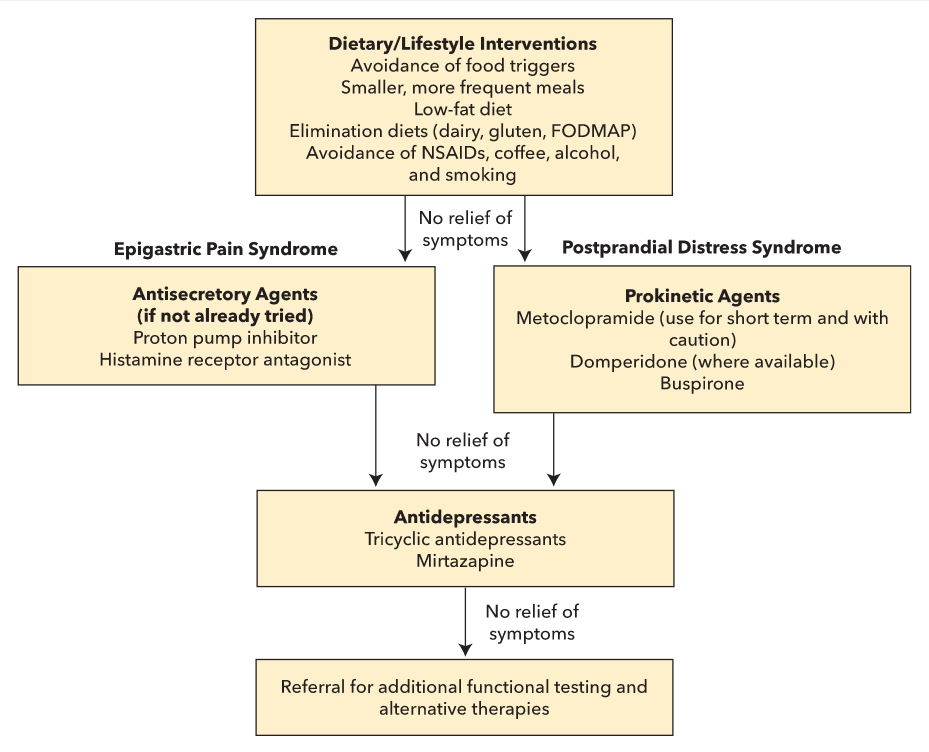

Management of dyspepsia is directed at treatment of the underlying cause. Patients who test positive for H. pylori should receive eradication therapy. If H. pylori testing is negative or H. pylori eradication fails to relieve the dyspepsia, an empiric trial of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) should be pursued for 4 weeks. Patients whose symptoms are not alleviated with PPI therapy should undergo further evaluation with an upper endoscopy. Patients diagnosed with functional dyspepsia after the exclusion of organic disease can be treated with a variety of interventions (Figure 8).

Treatment of functional dyspepsia.

FODMAP = Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, And Polyols.

Peptic Ulcer Disease

Clinical Features, Diagnosis, and Complications

The most frequently reported symptom of peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is epigastric pain, frequently described as worse during fasting and improved with eating or use of antacid or antisecretory therapy. Pain may be accompanied by other dyspeptic symptoms, such as early satiety, abdominal bloating, nausea, belching, or heartburn (from coexistent esophagitis). Epigastric pain may be minimal or absent in the elderly, immunosuppressed patients, and chronic NSAID users.

NSAIDs and H. pylori infection are the two most common causes of PUD, although idiopathic (NSAID-negative, H. pylori–negative) PUD is becoming more common in the United States. The causes of idiopathic PUD remain unclear; however, cocaine, methamphetamine, bisphosphonates, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, and stress have been implicated. Rare causes of PUD include gastrinoma (Zollinger-Ellison syndrome), systemic mastocytosis, α1-antitrypsin deficiency, COPD, chronic kidney disease, gastric cancer, gastric lymphoma, Crohn disease, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, or cytomegalovirus (in immunocompromised patients).

The diagnosis of PUD is most often made by upper endoscopy. Abdominal CT is the diagnostic study of choice for suspected perforating PUD, with a sensitivity of 98%.

Complications of PUD include bleeding, perforation, and obstruction. PUD is the most common cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Overt bleeding presents with melena, hematemesis, and/or hematochezia, whereas obscure bleeding presents with iron deficiency anemia and/or stool positive for occult blood. Perforation is likely to present with sudden, severe epigastric pain that can become more generalized, along with peritoneal findings. Symptoms associated with obstruction may include vomiting, early satiety, abdominal distension, and weight loss.

Management

Following confirmation of uncomplicated PUD by upper endoscopy, H. pylori infection should be treated if identified and eradication confirmed after treatment. If H. pylori testing is negative, a once-daily PPI should be initiated and any agent causing PUD (such as an NSAID) should be discontinued. Testing that is completed in the acute setting and has negative results should be repeated after discharge.

In patients with bleeding PUD, risk factors that increase the risk for recurrent bleeding and death include tachycardia, hypotension, age older than 60 years, hemoglobin level less than 7 g/dL (70 g/L) (8 g/dL [80 g/L] in patients with cardiovascular disease), and comorbid illness. Interventions to address the modifiable risks should be pursued before upper endoscopy.

Upper endoscopy should be performed within 24 hours. The use of PPIs before upper endoscopy reduces the need for endoscopic therapy only in patients with high-risk ulcer findings. An intravenous dose of erythromycin 30 minutes before upper endoscopy may reduce the need for repeat endoscopy by improving gastroduodenal visualization; however, it should not be done routinely, but rather when requested by the endoscopist. Nasogastric tube placement is not required before upper endoscopy.

In patients with bleeding PUD related to low-dose aspirin use for secondary cardiovascular prevention, aspirin should be restarted 1 to 7 days after cessation of bleeding. PPI therapy can be discontinued after confirmation of H. pylori eradication in patients with _H. pylori–_associated bleeding PUD. NSAIDs should be discontinued in patients with NSAID-induced bleeding PUD. If there is no effective alternative to NSAIDs, a selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor plus a once-daily PPI should be used. Patients with idiopathic ulcers that have bled should receive once-daily PPI therapy indefinitely because of the significant risk for rebleeding.

Repeat upper endoscopy is not performed routinely. Reasons for a follow-up upper endoscopy may include persistent symptoms after 8 to 12 weeks of therapy, ulcers of unknown cause, and if gastric ulcer biopsy was not performed during the initial upper endoscopy.

Perforated PUD is a surgical emergency with a mortality rate of up to 30%; older age, comorbidity, and delayed surgery confer increased risk. Prompt identification, urgent surgical intervention, and proper pre- and postoperative management of sepsis are essential. Postoperative upper endoscopy to rule out gastric cancer should be considered for patients with perforating gastric ulcers.

Gastric outlet obstruction resulting from inflammation or scarring at the pylorus or proximal duodenum should be biopsied at the time of diagnosis to exclude malignancy. For mild symptoms, PPI therapy, treatment of H. pylori infection if identified, and/or cessation of NSAIDs may be effective. For severe or persistent symptoms, endoscopic dilation should be pursued, reserving surgery for obstruction that persists after more than two attempts at endoscopic dilation.

Helicobacter pylori Infection

Indications for Helicobacter pylori Testing

Indications for H. pylori testing include active PUD, history of PUD without documented cure of H. pylori infection, gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, or history of endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Other conditions in which H. pylori testing should be considered include dyspepsia in patients younger than age 60 years without alarm features warranting early upper endoscopy, before long-term low-dose aspirin or NSAID use, unexplained iron deficiency anemia, and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura in adult patients with gastrointestinal symptoms. Routine testing for H. pylori is not indicated in patients with typical gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms, lymphocytic gastritis, hyperplastic gastric polyps, or hyperemesis gravidarum, or in asymptomatic individuals with a family history of gastric cancer.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of H. pylori infection can be made with gastric biopsies during upper endoscopy, or noninvasively using 13C-urea breath, stool antigen, or serologic testing. The 13C-urea breath and the monoclonal stool antigen are the preferred noninvasive tests because both have sensitivity and specificity greater than 95% for evidence of active infection. Serologic testing for IgG antibodies against H. pylori is the cheapest and most convenient method; however, it has the significant disadvantage of being unable to distinguish between active and previous infection. Although the negative predictive value of serologic testing is reasonably high, a positive serologic result in a population with low prevalence of H. pylori infection, such as in the United States, requires confirmation with the 13C-urea breath test, stool antigen test, or gastric biopsy. Also, conditions that lower the H. pylori density, such as PPI use, recent antibiotic use, atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, or mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, can result in false-negative results for any of the noninvasive studies. Serologic testing is most useful as an adjunct test in patients with bleeding PUD because of the decreased sensitivity of biopsy in the setting of acute bleeding. Any upper endoscopy for the evaluation of dyspepsia, or with the finding of gastric erosions or ulcers, should include gastric biopsies for H. pylori testing by histology or a rapid urea test.

Treatment

Any patient with a test result that is positive for active infection requires treatment with the goal of H. pylori eradication. The first course of treatment offers the best chance of eradication and should be carefully chosen. Several first-line treatments are available, with the choice based on resistance patterns of H. pylori, previous antibiotic use by the patient, and antibiotic allergies (Table 9). In most cases, duration of therapy is 14 days. Second-line therapy in the event of treatment failure should be for a minimum of 14 days, ideally using antibiotics different from those used for initial treatment (Table 10).

Eradication Testing

Testing for eradication of H. pylori should be done after completion of eradication therapy, using a 13C-urea breath test, fecal antigen test, or biopsies obtained during upper endoscopy at least 4 weeks after completion of eradication therapy. Serologic testing is not used to confirm H. pylori eradication because it can remain positive in the absence of active infection.

Miscellaneous Gastropathy

Atrophic Gastritis

Chronic atrophic gastritis can present as either an environmental metaplastic atrophic gastritis (EMAG), also called multifocal atrophic gastritis, or an autoimmune atrophic gastritis (AMAG). EMAG is the result of H. pylori infection, and typically improves after H. pylori eradication. AMAG is caused by autoantibody formation to parietal cell antigens, and is commonly associated with pernicious anemia and has no cure. The achlorhydria (reduced gastric acid production) from chronic atrophic gastritis can lead to iron deficiency, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, and enteric infections. The secondary hypergastrinemia associated with AMAG can promote the development of gastric carcinoid. Goals of therapy for patients with AMAG include the prevention of pernicious anemia and iron deficiency with vitamin B12 supplementation and iron replacement, and surveillance for gastric neoplasm. It is prudent to perform upper endoscopy and gastric biopsy at the time of pernicious anemia diagnosis to evaluate for these cancers; however, the benefit on ongoing surveillance endoscopy is unclear. Autoimmune-related pernicious anemia and associated iron deficiency anemia are likely to require lifelong vitamin B12 and iron replacement, respectively.

Intestinal Metaplasia

Gastric intestinal metaplasia is a preneoplastic gastropathy arising from chronic inflammation associated with H. pylori infection. As such, patients with gastric intestinal metaplasia should be tested and treated for H. pylori if the infection is identified. Other causes of chronic inflammation, including other gastric infections, chemical agents, and autoimmune disease, may also promote progression to gastric intestinal metaplasia. There is no conclusive evidence that long-term PPI use promotes the development of intestinal metaplasia. Gastric intestinal metaplasia is believed to be an intermediary stage in the multistage progression from chronic atrophic gastritis to gastric adenocarcinoma. If metaplasia is secondary to H. pylori infection, eradication therapy may decrease progression to gastric adenocarcinoma. Given the rarity of gastric adenocarcinoma in the United States, current guidelines recommend against the routine use of surveillance endoscopy in gastric intestinal metaplasia. Surveillance programs do exist in other parts of the world, and endoscopic surveillance should be considered in patients at increased risk (such as those with complete or extensive gastric intestinal metaplasia on endoscopy; those with a family history of gastric cancer; racial/ethnic minorities; or those who have emigrated from East Asia, Russia, or South America).

Eosinophilic Gastritis

Eosinophilic gastritis is a rare gastropathy characterized by infiltration of eosinophils in the stomach. Secondary causes of eosinophilia should first be excluded, including parasitic and bacterial infections of the stomach, inflammatory bowel disease, hypereosinophilic syndrome, myeloproliferative disorders, polyarteritis, allergic vasculitis, scleroderma, drug injury, and drug hypersensitivity. The cause of primary eosinophilic gastritis is unknown, but believed to be an allergic process. Symptoms vary widely based on depth of eosinophilia and organ involvement, as the small bowel may also be involved. Treatment includes avoidance of food allergens and use of elemental diets and/or glucocorticoids.

Lymphocytic Gastritis

Lymphocytic gastritis is a rare gastropathy typically presenting with mild, nonspecific dyspeptic symptoms and a normal-appearing stomach on endoscopy. On occasion, the stomach may have thickened folds covered by small nodules and aphthous ulceration. Celiac disease is the most common cause of lymphocytic gastritis. Other causes include HIV infection, Crohn disease, common variable immunodeficiency, and, rarely, H. pylori infection.

Gastrointestinal Complications of NSAIDs

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Upper gastrointestinal complications associated with NSAID use can occur with short- or long-term NSAID use and are dose dependent, with a linear increase in incidence over time with chronic NSAID use. Nearly 1% to 2% of chronic NSAIDs users suffer a clinically significant upper gastrointestinal event (such as a bleeding ulcer, perforation, or obstruction) annually. The rate of upper gastrointestinal adverse events rises to 14% for elderly NSAID users. The greatest risk factor for an NSAID-related upper gastrointestinal bleed is a history of gastrointestinal bleeding. Other risk factors are listed in Table 11.

The use of low-dose aspirin for cardioprophylaxis is associated with a two- to fourfold increase in risk for upper gastrointestinal complications including bleeding ulcer, perforation, and obstruction. Use of enteric-coated aspirin does not lower this risk, and an increase in aspirin dosage is associated with an increased risk for upper gastrointestinal complications.

Prevention of NSAID-Induced Injury

Treatment strategies for the prevention of NSAID-related upper gastrointestinal adverse events include the avoidance of NSAIDs, addressing modifiable risk factors, use of a selective cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitor, or coadministration of gastroprotective agents, such as PPIs, misoprostol, or H2 blockers. PPIs are the preferred gastroprotective agent for the treatment and prophylaxis of NSAID-related (including aspirin-related) upper gastrointestinal complications, and are specifically superior to H2 blockers in the prevention of PUD and bleeding related to low-dose aspirin use. Misoprostol may be used instead of PPIs in patients with intolerance or unwillingness to take PPIs. However, side effects of misoprostol, such as diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, and nausea, can be limiting, particularly at therapeutic doses, and it is contraindicated in pregnancy.

When coadministered with aspirin, a selective COX-2 inhibitor provides no advantage over an NSAID in the prevention of an upper gastrointestinal adverse event. Given the increased risk for PUD with the concomitant use of either an NSAID or selective COX-2 inhibitor with low-dose aspirin, at-risk individuals should receive gastroprotective therapy. Compared to an NSAID plus a PPI in patients at high risk, a selective COX-2 inhibitor plus a PPI offers a lower risk for perforation, obstruction, and bleeding, as well as for NSAID and COX-2 withdrawal due to gastrointestinal adverse events.

After an NSAID-induced bleeding peptic ulcer, the safest strategy is avoidance of future NSAID use. If an NSAID must be used, the combination of a selective COX-2 inhibitor plus a PPI provides the best gastrointestinal protection, as this combination is more likely to prevent a rebleed than a selective COX-2 inhibitor alone or an NSAID plus a PPI. A treatment approach based on risk for NSAID-related ulcer complications and the need for low-dose aspirin for cardioprophylaxis is provided in Table 12.

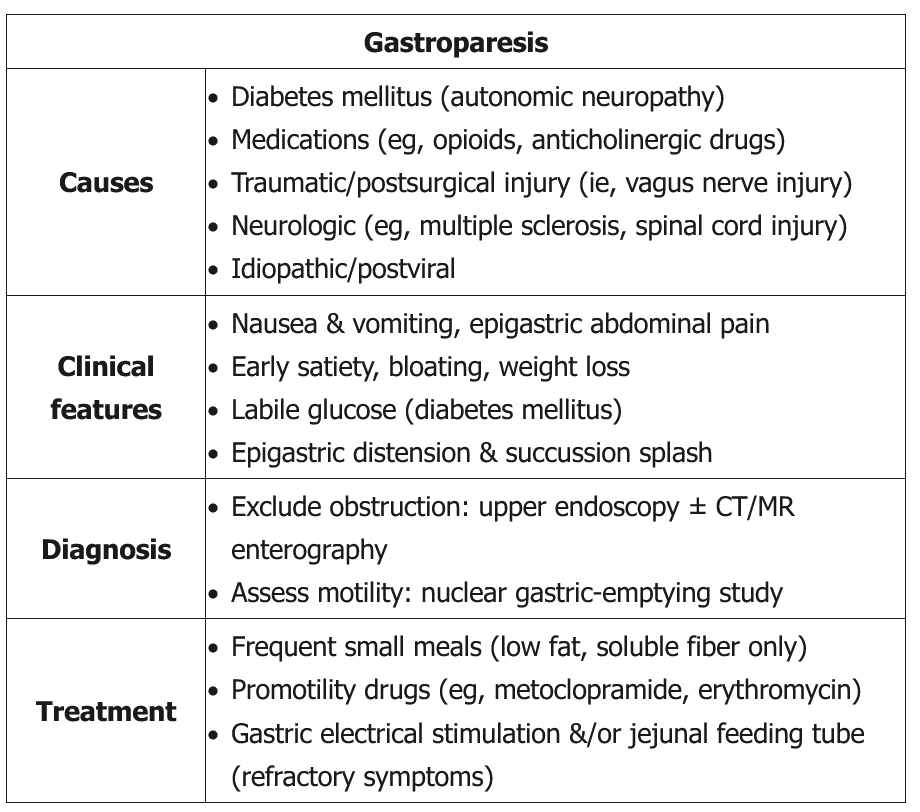

Gastroparesis

This patient's presentation (postprandial reflux, vomiting, succussion splash) is most consistent with impaired gastric emptying, which can be due to the following:

- Gastric dysmotility (eg, gastroparesis)

- Gastric outlet obstruction (eg, pancreatic cancer compressing the stomach, gastric polyp, stricture from peptic ulcer disease)

Although this patient likely has gastric dysmotility due to diabetic gastroparesis, a diagnosis of gastroparesis requires proving delayed gastric emptying in the absence of obstruction. Therefore, the best first step in the workup of any patient with impaired gastric motility is to exclude a gastric outlet obstruction with upper gastrointestinal endoscopy; this is particularly important in patients who have risk factors for peptic ulcer disease (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use). Sometimes further imaging is needed as well, such as CT/MR enterography to exclude a small bowel mass or other pathology.

Once gastric outlet obstruction has been excluded, the presence of delayed gastric emptying (eg, gastric-emptying scintigraphy showing >10% gastric retention 4 hr following a solid meal) must be proven to establish a diagnosis of gastroparesis. Once diagnosed, an evaluation for the underlying etiology, such as diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, and autoimmune disease, should occur. Gastroduodenal manometry and autonomic testing are sometimes used to distinguish between myopathic and neuropathic causes.

Presentation

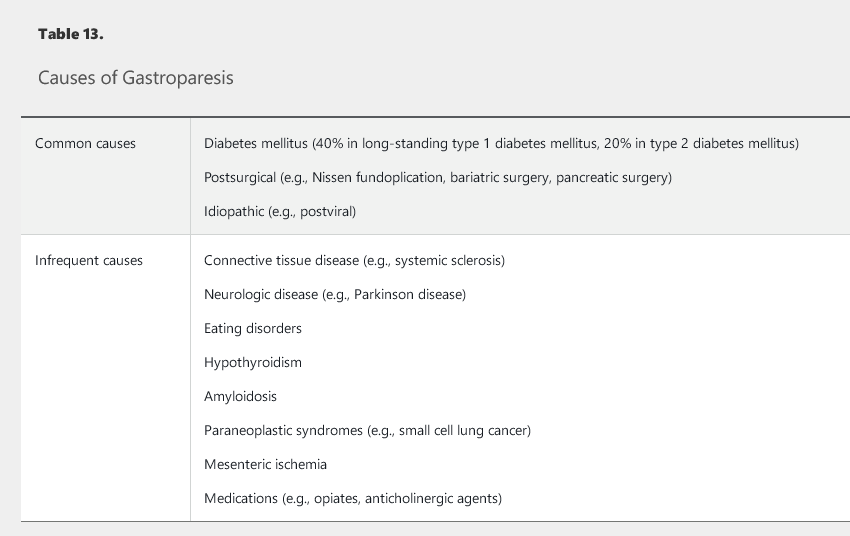

Gastroparesis is a heterogeneous clinical syndrome with three components to the diagnosis: the presence of specific symptoms, absence of mechanical outlet obstruction, and objective evidence of delay in gastric emptying into the duodenum. The most commonly reported symptoms in order of prevalence are nausea (90%), vomiting (84%), upper abdominal pain (72%), and early satiety (60%). Other symptoms may include abdominal fullness and bloating. Symptoms may be chronic or persistent, or may occur intermittently. More severe cases may involve weight loss and evidence of malnutrition and/or dehydration. A viral prodrome, such as gastroenteritis or respiratory infection before symptom onset, may suggest postviral gastroparesis, a condition that frequently resolves over time. Gastroparesis can result from a variety of causes (Table 13).

Diagnostic Testing

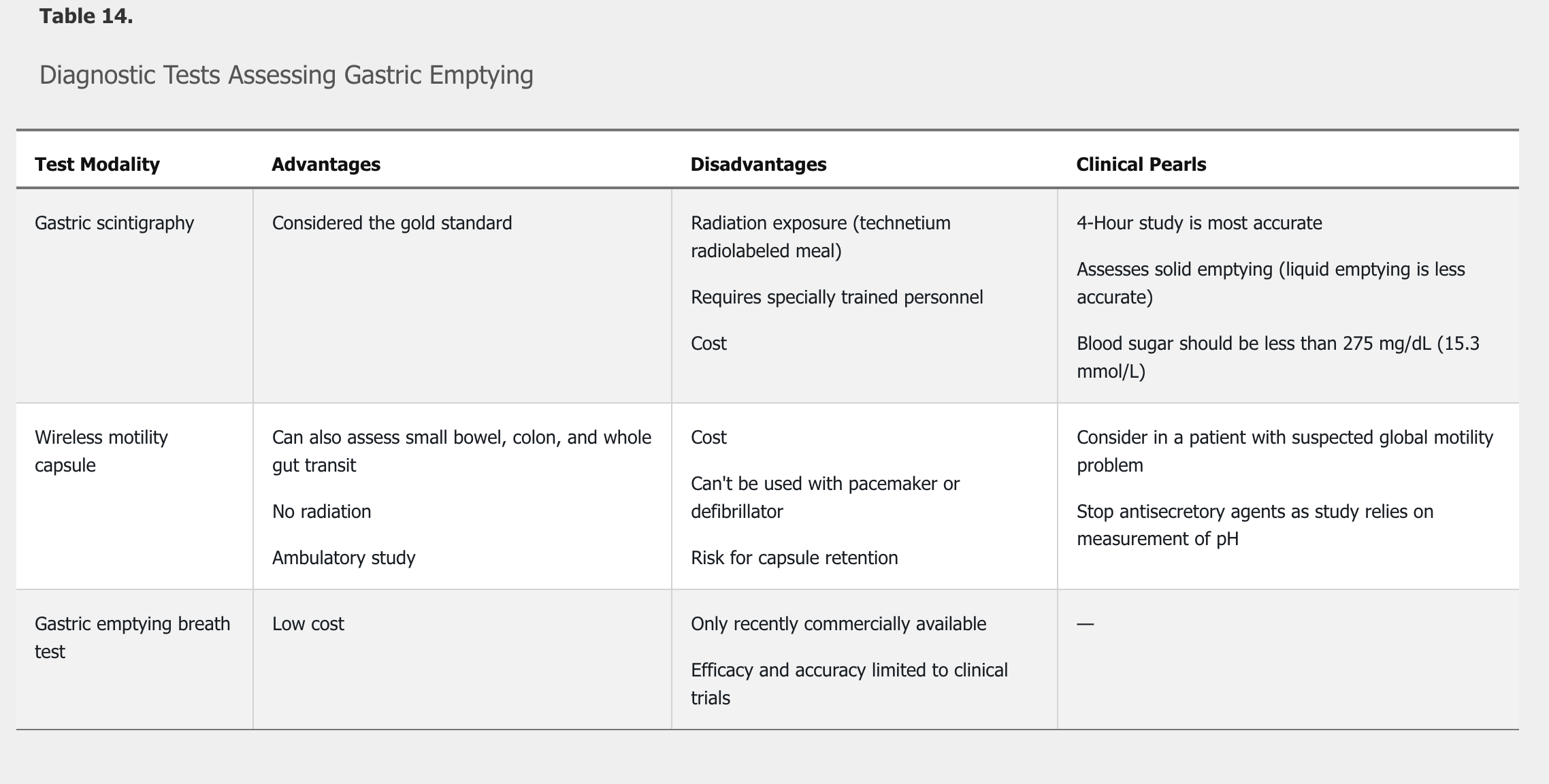

The first study performed to evaluate suspected gastroparesis is an upper endoscopy to exclude a gastric outlet obstruction. Once a structural cause for symptoms has been excluded, an objective test to assess gastric emptying is performed. There are three testing modalities available to assess gastric emptying: gastric scintigraphy, wireless motility capsule, and the radiolabeled carbon breath test using 13C-labeled Spirulina platensis (Table 14). Gastric scintigraphy is the most commonly used modality. Narcotic and anticholinergic agents must be stopped at least 72 hours before a gastric emptying study. Once delayed emptying is objectively confirmed, additional testing maybe required to determine the underlying cause of the gastroparesis.

Gastric emptying scintigraphy is the most appropriate next step in management. The diagnosis of gastroparesis requires: (1) the presence of specific symptoms; (2) the absence of mechanical outlet obstruction; and (3) objective evidence of delay in gastric emptying into the duodenum.

Management

The severity of gastroparesis-related symptoms does not correlate with the severity of delayed gastric emptying, particularly with regard to the symptoms of abdominal bloating and epigastric pain. This suggests that gastroparesis is not simply a motility disorder but one of altered sensation as well. Because poor glycemic control (blood glucose level >200 mg/dL, 11.1 mmol/L) can worsen symptoms as well as gastric emptying, tight glycemic control is the most important element of treatment of diabetic gastroparesis. Initial management also includes correction of dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities, and nutritional support if needed. Initial dietary intervention should consist of small, frequent meals that are low in fat and soluble fiber. Referral to a dietician may be beneficial.

Pharmacologic therapy is used to improve gastric emptying and to treat symptoms. Metoclopramide is the only prokinetic approved in the United States for the treatment of gastroparesis. To minimize the significant risk for neurologic side effects, including dystonia, Parkinsonian movements, and tardive dyskinesia, the lowest effective dose should be used. Therapy must be stopped immediately if neurologic side effects develop.

Erythromycin improves gastric emptying, but its use should be limited to the treatment of flares or short-term use (2 to 3 weeks) due to the risk for tachyphylaxis.

Antiemetics for treatment of nausea and vomiting as well as centrally acting modulators, including tricyclic antidepressants and mirtazapine, can also provide relief of symptoms but have no beneficial effect on gastric emptying.

Interventional therapy, such enteral feeding via jejunostomy, gastric stimulator placement, pyloroplasty, and subtotal or total gastrectomy, can be considered in patients who do not respond to dietary and pharmacologic therapy.

Gastric Polyps and Subepithelial Lesions

Gastric Polyps

Polyps in the stomach include fundic gland polyps, hyperplastic polyps, and adenomas. Fundic gland polyps and hyperplastic polyps account for 70% to 90% of stomach polyps. Fundic gland polyps are commonly seen in the setting of PPI use and are also found in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. All gastric polyps should be biopsied to determine polyp histology.

Hyperplastic polyps of the stomach are thought to have malignant potential, with 5% to 19% harboring dysplasia or malignancy. Risk factors for malignant potential of hyperplastic polyps include size greater than 1 cm and pedunculated morphology. All hyperplastic polyps greater than 0.5 to 1.0 cm in size should be resected.

Adenomas found in the stomach can be sporadic or associated with hereditary syndromes, including familial adenomatous polyposis and Lynch syndrome. Adenomas in the stomach should be resected and endoscopic surveillance should be performed 1 year after resection and then every 3 to 5 years thereafter.

Gastric Subepithelial Lesions

Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal tumors of the stomach. GISTs may present with symptoms, such as bleeding or abdominal pain, but are also found incidentally. Endoscopic ultrasonography is the best diagnostic modality for evaluation of a GIST. High-risk features on endoscopic ultrasonography include size greater than 2 cm, lobulated or irregular borders, invasion into adjacent structures, and heterogeneity. Biopsies of a GIST can be done, but the high-risk endoscopic features are better predictors of malignant potential. Treatment consists of surgical excision if the GIST is symptomatic or high-risk features are present. For GISTs without high-risk features, yearly endoscopic surveillance is indicated. See MKSAP 18 Hematology and Oncology for staging and treatment of GISTs.

Carcinoid Tumors

A carcinoid tumor is a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor originating in the digestive tract, lungs, or, rarely, the kidneys or ovaries. Carcinoid tumors can be encountered throughout the gastrointestinal tract, including the stomach. They may present symptomatically or may be found incidentally. Carcinoid tumors are usually sporadic but can be seen in the setting of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, atrophic gastritis, and rare syndromes, such as multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and neurofibromatosis type 1. Carcinoid tumors are classified by their size, number, and anatomic distribution. Management includes endoscopic surveillance for lesions smaller than 1 cm in size, especially when multiple lesions are present. Endoscopic or surgical excision is indicated for carcinoid tumors with high-risk features, such as solitary lesions not found in the setting of atrophic gastritis or Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. See MKSAP 18 Hematology and Oncology for treatment of gastric neuroendocrine tumors.

Gastric Adenocarcinoma

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Stomach adenocarcinoma has an incidence rate of 6.7 in 100,000 persons and a mortality rate of 3.4 per 100,000 persons in the United States. Rates have steadily decreased since the 1990s. There are two types of gastric cancer: intestinal-type, which is more common, and diffuse-type. H. pylori is a recognized risk factor for both types of cancer. Other risk factors primarily associated with intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinoma include male sex; ethnicity (incidence is highest in persons of Asian and Pacific Island descent, and mortality is highest in non-Hispanic White persons); geography (the highest rates worldwide occur in Asia, Eastern Europe, and Central and South America); diet high in smoked, salted, and pickled foods as well as nitrates and nitrites; smoking; and obesity. Additional risk factors include previous stomach surgery, pernicious anemia, and hereditary syndromes such as hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (associated with the diffuse type), Lynch syndrome, and familial adenomatous polyposis. Gastric intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia are also risk factors for gastric adenocarcinoma.

Screening and Surveillance

There is no recommendation for population-based screening for gastric adenocarcinoma in countries with a low incidence of gastric cancer, such as the United States. If intestinal metaplasia with high-grade dysplasia is identified, it should be resected because 25% of cases progress to adenocarcinoma. Screening and surveillance is indicated for patients with familial adenomatous polyposis and Lynch syndrome.

"The patient's presentation is suggestive of gastric cancer, specifically diffuse gastric cancer. Proposed criteria for selection of patients for genetic testing for hereditary diffuse gastric cancer include the following: family members with two or more documented cases of gastric cancer in first- or second-degree relatives, with at least one diffuse gastric cancer diagnosed before age 50 years; family members with multiple lobular breast cancers with or without diffuse gastric cancer in first- or second-degree relatives; and, a personal diagnosis of diffuse gastric cancer before age 35 years from a low-incidence population such as in Canada and the United States. Based on the patient's young age and history of multiple family members with gastric and lobular breast cancer, hereditary diffuse gastric cancer is a likely diagnosis. The best diagnostic test for gastric cancer is an upper endoscopy with multiple biopsies of the stomach. The syndrome of hereditary diffuse gastric cancer is associated with mutations in the CDH1 gene. The risk for diffuse gastric cancer approaches 80% in carriers of the mutation, and prophylactic gastrectomy is recommended in mutation carriers who have not developed gastric cancer."

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

Symptoms of gastric adenocarcinoma may be vague. They include poor appetite, weight loss, abdominal pain, early satiety, nausea, and vomiting. Signs of gastric adenocarcinoma include iron deficiency anemia. Diagnosis is typically made by upper endoscopy with biopsies.

Gastric Surgery Complications

Partial or complete gastric resections are performed for benign and malignant disease. The extent of resection, type of reconstruction, and nature of the disease affect postoperative morbidity and mortality. Partial gastric resection allows for preservation of some function of the stomach, but in the setting of malignancy, it requires lifelong surveillance of the remaining stomach for recurrence. Patients who undergo partial gastrectomy for benign disease have an increased risk for cancer in the gastric remnant 15 to 20 years after surgery, with reported frequency ranging from 0.8% to 8.9%.

Dumping syndrome, which results from rapid gastric emptying after gastric surgery, can cause significant postprandial gastrointestinal and vasomotor symptoms. Clinical features of early dumping syndrome occur within 30 minutes of eating due to gastrointestinal hormone hypersecretion, autonomic dysregulation, and bowel distention. Symptoms include palpitations, flushing or pallor, diaphoresis, lightheadedness, hypotension, and fatigue, followed by diarrhea, nausea, abdominal bloating, cramping, and borborygmus. Late symptoms occur 1 to 3 hours after meals because of reactive hypoglycemia and can include decreased concentration, faintness, and altered consciousness. In severe cases, protein-wasting malnutrition can occur. It is estimated that 25% to 50% of all patients who have undergone gastric surgery experience some symptoms of dumping syndrome, but severe, persistent symptoms occur in only about 10%. Oral glucose challenge testing is useful to make the diagnosis, with a sensitivity as high as 100% and a specificity of 94%.

SIBO: Unlike in dumping syndrome, symptoms are not immediately related to eating and are not associated with prominent vasomotor symptoms such as palpitations, tachycardia, diaphoresis, and lightheadedness.

First-line treatment for dumping syndrome is dietary, with smaller, more frequent meals and ingestion of liquids after meals. Decreasing carbohydrate intake, especially simple carbohydrates, and increasing protein and fiber intake may also alleviate symptoms.

Acarbose, an α-glycosidase hydrolase inhibitor that interferes with the digestion of polysaccharides to monosaccharides, can be used for late symptoms of dumping syndrome. Other pharmacologic therapies include anticholinergics to slow gastric emptying, and antispasmodics. Severe cases of dumping rarely require octreotide. If a trial of subcutaneous injections is effective, monthly intramuscular injections of long-acting octreotide can be used.